There will be a great congregation of friends and activists inside the Great Hall at the Cooper Union tomorrow evening at six o’clock. There they will be celebrating the rich life of Harry Wieder, cut short, shockingly, in an accident in April.

Harry was a familiar friend and powerful advocate of many progressive causes, so I expect the room will resemble a portrait of the face of New York grassroots activism (of almost every sort) as it operated over the last few decades.

I also expect that this memorial will not be a lugubrious affair. Harry meant a lot to the people who shared his life and his dedication. But we also knew how to share in laughter, and there should be plenty of that tomorrow.

Harry was also completely familiar with the historic Great Hall, not least for his regular attendance at ACT UP meetings, which continued while they were being held there in the early 90’s. It was a time, difficult to imagine today, when the press of hundreds of AIDS activists (I’m sure I remember hearing the number 700 one week), attracted by the urgency of the issues and the energy of the coalition, had forced a move from the pre-restoration Center to a larger venue. It was Cooper which welcomed us.

I’ve been back many times since those years, and Barry and I will be there tomorrow.

Speaking of ACT UP, and the kind of energy which seems in scarce supply these days, the incredibly-important ACT UP Oral History Project has just added 14 new interviews with ACT UP activists and add 9 important video clips and transcripts to its web site. Visit, rummage around, then go out and change the world.

While working on this post I once again found myself Googling for an image of “Harry Wieder”; there aren’t a great number, and most of them are mixed in with a much, much larger number of images of “Prince Harry”. Our Harry would love that.

[image via pinknews]

Category: History

tomorrow is the last chance to “Escape from New York”

An Xiao The Artist is Kinda Present [still from five-hour performance]

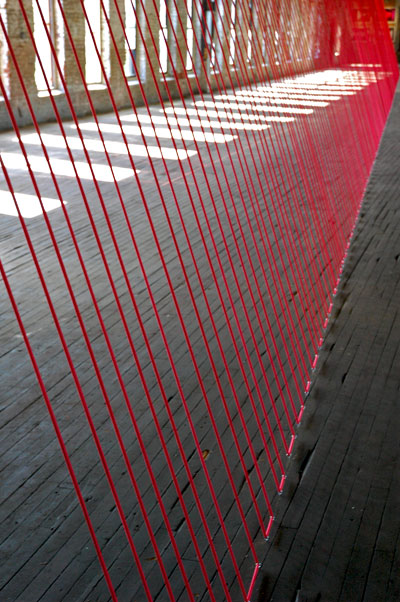

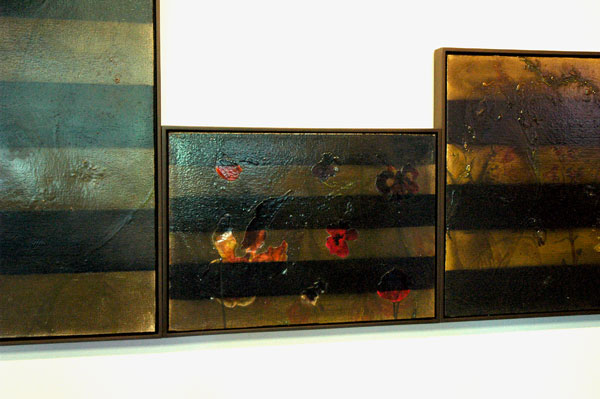

Tomorrow is the last day for the tonic and pleasures of the huge-scale Paterson, New Jersey installation, “Escape from New York“, and I just realized that I hadn’t uploaded any images yet. The show, curated by Olympia Lambert, is a treat on its own, but added to that, for those willing to leave familiar streets, are the curiosities (nineteenth-century usage) represented in the numerous and varied reminders of the town’s industrial and social history.

The old core of Paterson still displays countess monuments to its former wealth, most of the public, banking and commercial buildings plainly marked to show they were erected at the turn of the twentieth century.

There are also an amazing number of nineteenth-century mill buildings just beyond the center, many of them handsomely restored (and presumably looking for artists), One of them (unrestored) shelters the work of the 43 “Escape” artists Lambert has collected. It and its dozens of sturdy brick neighbors share an old mill race and are perched below tree-covered hills just below a surprisingly idyllic Passaic Falls.

The cataract is the the second-highest large-volume falls on the U.S. East Coast, which accounts for Paterson’s importance 200 years ago. Okay, the day we were there we saw a wedding party being photographed before it on a wide grassy ledge while we watched from above. Together with the architectural treasures the falls offer an additional incentive for a rail trip, a brief, comfortable ride on NJ Transit from Penn Station.

If you miss your own escape to New Jersey and these combined pleasures, there will be at least a chance to see some of the work in Manhattan in July (minus Paterson, of course). Lambert is putting the finishing touches on arrangements for “Return to New York”, to be installed at HP Garcia Gallery July 7-31.

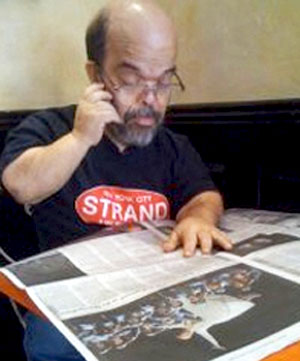

Alex Gingrow Younger Than Jesus made me throw . . .

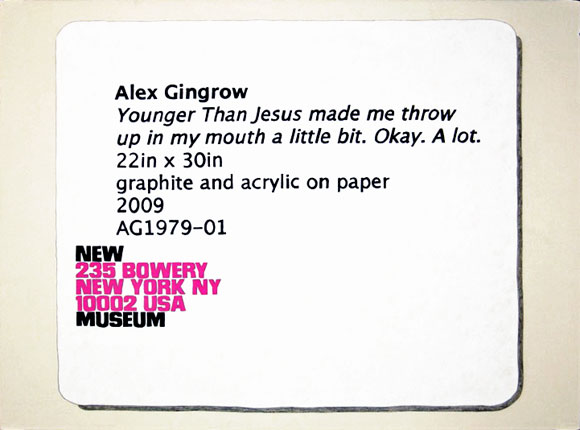

Nicholas Fraser The Paterson Project [detail]

Peter Soriano Other Side # 82 (MEC)

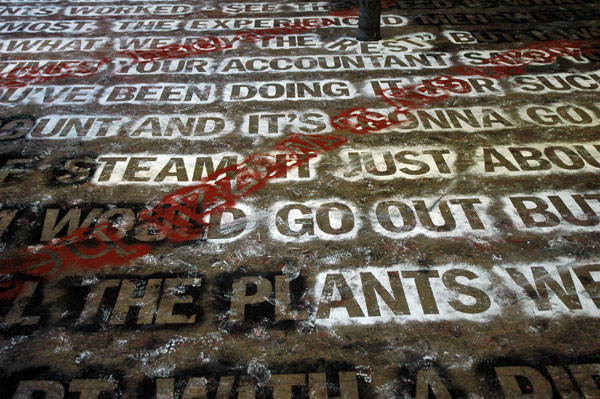

Man Bartlett circle drawing XII – rendition above pointpiece II – constant

Thomas Lendvai Untitled ([large detail]

Tamas Veszi Dark Matter [detail]

Lagniappe: An abbreviated look at a few of the mills, and the falls:

the corner of Spruce and Market, at dusk on a Saturday

the footbridge is historically the eighth on the site

[image of “Younger Than Jesus made me throw . . . ” from the artist’s site]

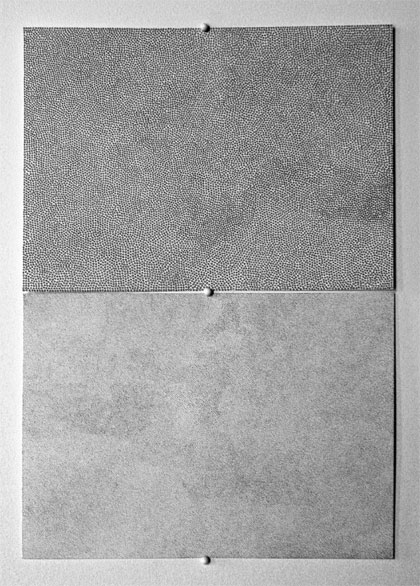

Manhattanhenge, from its western, 23rd Street stones

looking at the light cast from the west toward the stones to the east

As I prepared to leave the apartment this evening to go to the market, Barry reminded me that the phenomenon known as Manhattanhenge was about to light up our east-west street in its semiannual visitation. He said he’d heard on Twitter that it would take place precisely at 8:17. At that moment it was only 8:05, but as I didn’t know exactly what I would see when I got outside, I immediately headed out the door.

There I found that our doorman already knew all about our modest urban astronomical occasion, just as he always seems to know everything that goes on inside the building and anywhere in its proximity, so I didn’t have the satisfaction of inducting a new member into the cult. I then learned that, if anything, I may have been a moment too late rather than too early. The sun seemed to have already hidden itself somewhere in the Hudson River, but its corona was centered on the street axis and was still able to impede a direct glance.

I turned around to see what the eastern axis of the street might look like, stepped into the middle of the holiday-emptied six-lane thoroughfare, and snapped the picture above. Just as I got to the corner of Seventh Avenue (it was now 8:17 exactly), where the traffic signal was momentarily arresting the progress of the few east-west vehicles, a dozen or so pedestrians suddenly appeared in the crosswalk out of nowhere. Everyone seemed to have a camera and was snapping pictures of the setting sun, all the while totally ignoring the rich golden light momentarily transforming everything behind them, even to the white lane-dividing lines on the pavement.

I’m thinking the original stone-age celebrants on the Salisbury Plain would also have been more interested what the stones made of the sun’s rays running east, but there’s no way to know for sure. As I told my friend at the front desk, nobody stayed around to tell us.

and looking at the sun positioned in the portal between the western stones

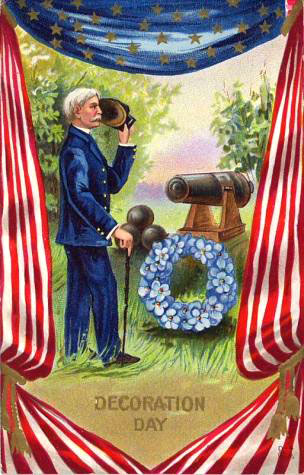

the real meaning of Memorial Day (or Decoration Day)

but where’s the gray, and, for that matter, the colors of our countless other fallen foes?

And it’s not for generals.

It seems Memorial Day is not supposed to be just about hot dogs, the Indianapolis 500, or summer whites. In fact the holiday formerly known as Decoration Day (the official name by Federal law until 1967) wasn’t even originally owned by war veterans. While today it commemorates Americans who died in any war throughout our extraordinarily-aggressive, warlike history, it was first enacted in response to the horrors of a civil war. The date itself, now established as the last Monday of May, was originally determined by the month of the final surrenders which marked the conclusion of the American Civil War.

But its disjointed history is actually far from the tidy story which an official declaration might seem to suggest.

What became Decoration Day, and eventually Memorial Day, had many separate origins. Towns in both the North and the South were already memorializing their recent war dead, and “decorating” their newly-dug graves, in spontaneous observances in the years before the 1868 official proclamation by General John Logan, the last national commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, in his “General Orders No.11”.

The holiday the general created was first observed on May 30, 1868. Flowers were placed on the graves of both Union and Confederate soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery. That cemetery, incidentally, was located on land the U.S. government had appropriated from Robert E. Lee at the beginning of the war, a development likely to have made an significant impression on the defeated South as much as on the Lee family itself.

Within two decades or so all of the northern states were observing the new holiday, but the South refused to acknowledge it. This should not have surprised anyone, either then or since. Even though the date May 30 had been picked precisely because it was not associated with any battle or anniversary, the observance itself was tainted by its association with the victorious and hated Union.

The various states of the old Confederacy continued to honor their own dead, on separate days, until after World War I, when the holiday was broadened to include not just those who died fighting in the Civil War but Americans who died in any war. Even then, most of the states of the old South still maintained separate days for their own dead, and do so to this day, although with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

I checked into this history yesterday when I was trying to decide whether I could honorably display the antique 48-star flag I’ve had for almost 40 years (antique in fact when I acquired it). I had kept it in a Chinese camphor-wood trunk for decades because our flag had come to be associated almost entirely with American jingoism; it had been hijacked by the crazies on the Right. Although I still had my doubts about the direction of this country even after Obama’s 2008 victory, I pulled the old banner out and hung it in the apartment last year, on the day of his inauguration, and again a few months later on July 4th.

Bush’s wars have now become Obama’s wars, and my very tentative interest in flag-waving, even flag-hanging, has (please excuse the choice of word) sort of flagged, although I still find things to love about this increasingly dysfunctional country.

When do we get a holiday celebrating the peacemakers? Of course that’s entirely a rhetorical question, coming from a citizen of a country which has almost never not been at war somewhere.

I went to Wikipedia in my search for a quick answer to my question about the original significance of the day we celebrate today mostly as just another excuse for a long weekend. There I learned that one time the holiday many originally associated with uncomplicated patriotic sacrifice did not mean the same thing for everyone, even in the 1860’s. In the Wikipedia entry for “Memorial Day: History”, I found this very moving and evocative window onto an America which was cursed to know war far better, and was far more weary of and horrified by it than our own:

At the end of the Civil War, communities set aside a day to mark the end of the war or as a memorial to those who had died. Some of the places creating an early memorial day include Sharpsburg, Maryland, located near Antietam Battlefield; Charleston, South Carolina; Boalsburg, Pennsylvania; Carbondale, Illinois; Columbus, Mississippi; many communities in Vermont; and some two dozen other cities and towns. These observances coalesced around Decoration Day, honoring the Confederate dead, and the several Confederate Memorial Days.

According to Professor David Blight of the Yale University History Department, the first memorial day was observed by formerly enslaved black people at the Washington Race Course (today the location of Hampton Park) in Charleston, South Carolina. The race course had been used as a temporary Confederate prison camp for captured Union soldiers in 1865, as well as a mass grave for Union soldiers who died there. Immediately after the cessation of hostilities, formerly enslaved people exhumed the bodies from the mass grave and reinterred them properly with individual graves. They built a fence around the graveyard with an entry arch and declared it a Union graveyard. The work was completed in only ten days. On May 1, 1865, the Charleston newspaper reported that a crowd of up to ten thousand, mainly black residents, including 2800 children, proceeded to the location for included sermons, singing, and a picnic on the grounds, thereby creating the first Decoration Day

So, the real meaning? I don’t think we have agreement even now, and for myself I haven’t yet decided whether to pull that faded old cloth from the trunk tonight.

[image of pre-WWI Decoration Day postcard from vintagepostacards]

Dominus totally gets Harry Weider, in today’s Times

Harry Wieder, above at lower right, at a press conference calling for wheelchair access seven days a week to the James A. Farley Post Office. [Times caption]

Today’s New York Times will include this lovely, absolutely lovely piece about Harry Wieder (which the paper unfortunately burdened with a totally lame headline*) by Susan Dominus: “Remembering the Little Man Who Was a Big Voice for Causes“.

He sometimes attended seven or eight meetings in a day, even if he snored his way through one or two of them. His friends joked that he must have a clone � �but why would anyone clone someone that strange?� Mr. Wasserman [Marvin Wasserman, a longtime ally and occasional victim] said.

*

I dunno, but I think I actually prefer, “Gay dwarf activist killed by New York taxi“, the headline I saw two days ago on an Australian site.

[Michael A. Harris image from the Times site]

Harry Wieder (1953-2010)

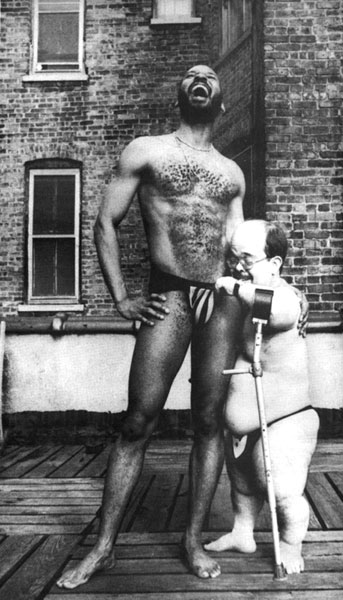

Harry was always an activist (here he is saying hello to the late Keith Cylar)

ADDENDA: I’ve now located* the original full image of the photograph I included above when I first did this entry, as well as the text which accompanied it, from a pre-summer issue of OutWeek published almost twenty years ago; this is Keith Cylar and Harry Wieder’s reply to the photographer and activist Michael Wakefields’s question about their ideal getaway:

“We would live in a world where we would then have the freedom to do more than just fantasize, where our fight to end AIDS has brought a reality, and there are countless sexual possibilities, especially for a militant sexual dwarf”

I’ve also added an image further into the entry, of Harry inside the maw of the beast, an ACT UP Monday night meeting

He described himself as a “Disabled, gay, Jewish, leftist, middle aged dwarf who ambulates with crutches”, but Harry was much more. He was the essential activist, and he was much loved.

I first met him through ACT UP, where I sat next to him at a Monday night meeting, and after that he seemed to be everywhere, especially wherever there was something to be said to power. I was deeply proud to call him a friend.

I hadn’t yet heard his own multifarious description of himself, but as I came to know better both the man and his work I watched his identity as an activist and as a man gradually enlarge in my own consciousness. Eventually I seemed to have assembled an image of all of his various hats and identities on my own, even adding “person of color” in my enthusiasm. I can’t account for that add-on. Harry might have been a bit “swarthy”, but I think it was his compassion and his natural affinity for the issues which affected blacks, or maybe there was even an ambiguous word from Harry himself. Then, only years later, when he told me where he then lived on the Lower East Side, in a home for the deaf, did I realize that his physical challenges included a hearing disability.

The news magazine OutWeek called Harry a “militant sexual dwarf” in a 1991 article which included the photo above. He’s seen peeking into the swimsuit of Keith Cylar, one of the co-founders of Housing Works. Barry remembers, “he was [certainly] aggressively flirtatious”.

We all loved him.

During all of his active life he worked to improve transportation for all so there was more than a little irony in the fact that he was struck down the night before last by a taxi on Essex Street, on the Lower East Side where he lived. It’s one of the most dangerous of the stretches which had attracted his latest traffic-control activism, virtually up to the moment of his death. He was leaving a regular meeting of Community Board 3, one of several groups which has been concerned with the neighborhood’s safety.

Board 3 will be joined by Community Board 2 at a public hearing scheduled by the NYC Department of Transportation for next Thursday on the issues of traffic and safety in the Village and the Lower East Side. Harry will certainly be a part of it.

Harry, waving from the front row during a 1990 ACT UP meeting [detail in a still from a video]

For more details: DNAinfo; The New York Post; Wall Street Journal (blog); the Lo-Down; Gothamist; The Edge (for starters)

*

EDIT: When I first published this post I was unable to locate Michael Wakefield’s original, uncropped image, but Bill Dobbs located it in the OutWeek archive and pointed me to it (it’s on page 36); it now appears here at the top

[first image by Michaeld Wakefield from the OutWeek archive; the second from James Wentzy]

8th anniversary of jameswagner.com

Today is the eighth anniversary of this blog.

I said it last year, and I’m delighted and incredibly privileged to say it again: This is also the anniversary of what turned out to be the most important event in my life, the night Barry and I met (now nineteen years ago).

Last year I also wrote, looking at the world outside our circle of close friends, that I was “more upbeat about the world” than I had been the year before, the eighth year of our second Bush, adding, “but only a bit”. That hasn’t changed, a bit.

And happy birthday, Paddy Johnson!

[the image is of a portion of the street number on the glass above one of the Art Deco entrances of the former Port Authority Commerce Building (1932), 111 Eighth Avenue the wall seen several feet behind the glass is covered with gold leaf]

Powhida: “No artist should have to watch this”

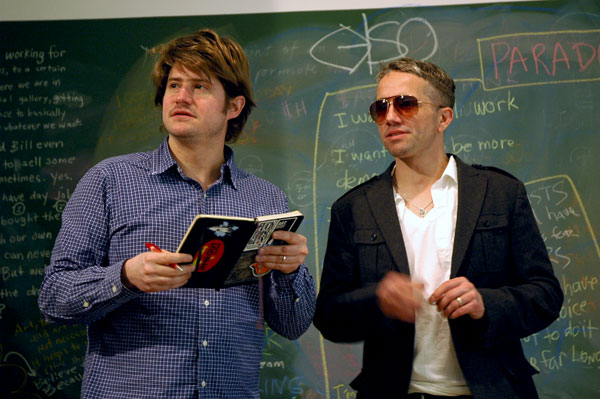

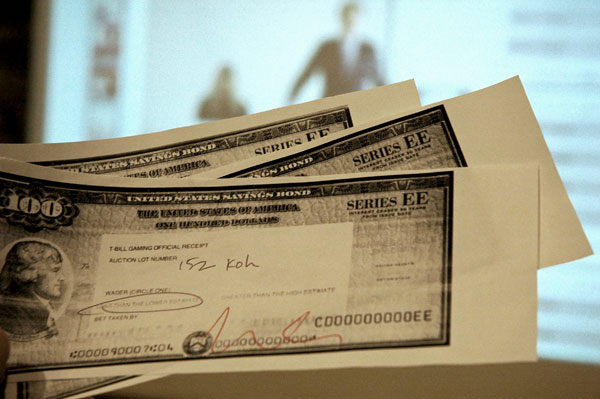

all heck breaks loose as Powhida exceeds the estimate

A number of art enthusiasts found their way to Winkleman gallery, and a Saturday in “#class“, this past weekend to take part in the (unbilled) “T-Bill Gaming” event. Tom Sanford and William Powhida had set up a projector and screen linked to a laptop, allowing gallery visitors follow the Phillips de Pury auction, “NOW: Art of the 21st Century“, in a live simulcast which began at noon.

Fans were invited, Sanford’s own blog had announced, to participate in a “relational aesthetics art project” involving “the sometimes-overlooked art of book making”. We had been invited to “watch the excitement unfold as shadowy and anonymous international art patrons determine the actual market value, not only of the works, but also of the hundreds of artists themselves!”

Fully in the spirit of the month-long project created by Powhida and Jen Dalton, the installation was described as an attempt “to make the world of contemporary art auctions more accessible to the Average Joe on the streets of Chelsea.”

The excitement in the gallery was building for hours as the auctioneer moved closer and closer to lot #257, a drawing by Powhida, “Untitled (Dana Schutz), which the artist had donated to a Momenta Art benefit five years ago. All heck broke loose when it went for $1,900 ($2,375 including 20% premium, and before taxes). The piece exceeded the high end of the auction house estimate. Since only a few years earlier someone had taken it home for $150, it certainly represented a good “investment” for its original owner, even if neither its author nor the non-profit space to which he had gifted it shared one penny of the bounty.

At some time in the midst of the excitement buildup the artist himself was heard to say:

No artist should have to watch this

For the artists and their friends and confederates in class that afternoon it was good fun, but mixed with the fun were melancholy thoughts framed by the sudden and direct confrontation with the reality of the art market. Inside the auction gallery however it all appeared to be only about money.

I’m sure we all had far more fun in class than did the crowd a few blocks south. I have a decent amount of experience with New England antique and estate auctions, and some familiarity with New York art auctions produced by a slightly less prestigious house than this one. I had always associated auctions with great fun and drama, even for the parsimonious participant, so I was shocked at how hurried and perfunctory the proceedings were on Saturday. Not a whit of drama – and no wit – came from the podium. The only excitement generated by the house (as opposed to that created by our own party on 27th Street) happened when the man in the $5000 suit, who normally finds himself selling off Picassos and Rauschenbergs, started the bidding on one item at $9 (it finally sold for $100).

the gamers

bets placed

the board

Yevgeniy Fiks names names in Communist Tour of MoMA

Diego Rivera Agrarian Leader Zapata 1931 fresco 7′ 9.75″ x 6′ 2″ [large detail taken from a slightly oblique angle, of the painting in MoMA’s collection]

Of course there was Rivera, and Kahlo, but most of the other committed pinko commies hanging around inside the Museum of Modern Art have been largely hidden from our history, from the institutional history of MoMA, and from the history of the art and the artists themselves.

Leading a tour of the Museum on 53rd Street this past Monday, artist and teacher Yevgeniy Fiks started to sort things out for the record. Barry and I were extremely fortunate to be a part of the discreet group of enthusiasts which he directed in a “Communist Tour of MoMA”.

One of my favorite parts? Enjoying the fact that any number of other museum visitors who happened near us were learning more than they had bargained for when they walked into the galleries of the permanent collection that afternoon.

If you missed the road trip clear your calendar for Fiks’ presentation, “Communist Modern Artists and the Art Market” at Winkleman gallery March 12, another event in William Powhida and Jen Bartlett’s month-long project, “#class“.

I’ve uploaded below images taken at a few of our stops (devotions, secular “stations”), and Barry has a more narrative report, assembled from his notes, on his own site.

Jacob Lawrence

Jackson Pollock

Henri Matisse

Marc Chagall

BHQF’s “We Like America” at Whitney 2010 Biennial

Bruce High Quality Foundation We Like America and America Likes Us 2010 vehicle and educational implements, dimensions variable [detail of installation]

ADDENDUM: [April 30, 2010] The entire sound video projected onto the inside of the windshield can be viewed here on vimeo, although as the April 20 comment at the bottom of this post (which alerted me to the link) says, it’s not quite the same isolated from the ambulance/hearse; the experience of the darkness of the installation itself, the imperfect acoustic of the space, and the murky projection, can’t really be reproduced on a computer screen.

I feel good about the Whitney 2010. While I like excitement, I resist hype like the plague. This Biennial has been accompanied by neither, which at the very least gives visitors a better chance to experience the individual works for themselves, and unencumbered with a theme. There is some very good, even awesome work on the three floors of the exhibition I saw at the preview (the floors not devoted to favorites from earlier years), but for me none of them had so fundamental an impact as the Bruce High Quality Foundation installation, “We Like America and America Likes Us”.

In “Art Class“, a 2007 piece published on Artnet, Ben Davis had described Picasso’s “Guernica” as “the most successful political image of the 20th century”. His argument was that isolated artistic gestures cannot resolve social contradictions “without any social movement backing them up to give them force”, continuing:

This does not mean that art or artists cannot play any political role; it is just that some model besides the middle-class one of “my art is my activism” is necessary, one based on concrete solidarity and practical action. Picasso�s Guernica is the most successful political image of the 20th century. Guernica, in fact, embodies the fact that art�s political value is determined in its relation with mass struggle, not in its individual content — the imagery of the painting, moving as it is, is completely drawn from a vocabulary of forms Picasso had already developed in previous work. Yet, during the Spanish Civil War, after its appearance at the Spanish Republic�s booth at the 1937 World�s Fair, Guernica was literally removed from its stretchers, rolled up and toured internationally to win support for the Republican cause. In England, visitors brought boots to send to the front.

The Bruce High Quality Foundation seems to be taking a different route with its own institutional, social and political critique, probably one more suited to our own politically-lethargic times. Bruce’s confrontations with our own tropes have been found just about everywhere: on our streets, our waters, our public plazas, even inside the galleries and expositions of the system they speak to.

I have to confess to a penchant for political art, and to a number of years spent in sort of a groupie relationship to this arts collective, and yet “We Like America and America Likes Us” is one of the most affecting works, in any genre, I’ve ever encountered. Where do we bring our allegorical boots?

We are all wounded, wrapped in felt. Are we inside an ambulance or a hearse? What is to be done?

Like much of what Bruce does, it’s not conventionally “beautiful” – except as truth is beauty, and yet the incredibly elegiac recorded remembrance of “America” which accompanies the fast video montage of heterogeneous clips projected onto the tall Cadillac windshield is riveting, and profoundly moving.

I don’t know the length of the loop (and there was no indication on the museum’s wall text); but for all I know it could be as long as the melancholy story it tells.

Especially for those who will not be able to visit the Whitney, I have some excerpts. The text, recited by a luscious, soothing female voice, begins:

We like America. And America likes us. But somehow, something keeps us from getting it together. We come to America. We leave America. We sing songs and celebrate the happenstance of our first meeting � a memory reprised often enough that now we celebrate the occasions of our remembrance more often than their first cause.

And a little later I listened as the gender pronouns slithered over each other in ecstasy, and in sorrow:

We wished we could have fallen in love with America. She was beautiful, angelic even, but it never made sense. Even rolling around on the wall-to-wall of her parents� living room with her hair in our teeth, even when our nails trenched the sweat down his back, and meeting his parents, America stayed simple somehow. He stayed an acquaintance, despite everything we shared. Just a friend. We could share anything and it would never go further than that.

No one really knows how love begins. A look on his face one time after we�d made love � a text message too soon after the last one. When did we become a thing to hold on to rather than just something to hold? We didn�t know America was in love with us until it was too late. Maybe we couldn�t have done anything about it anyway. America fell in love with the idea of us, with some fantasy of us, some fantasy of what America and us together would be, before we had a chance to tell him it could never work, we weren�t ready for a relationship, we weren�t comfortable being needed, we didn�t have the resources to be America�s dream.

It wasn�t easy letting America down. As we stuttered through our rehearsed speech we watched the change on her face. We could see the zoom lens of her attention clock away. We could feel ourselves receding back into the blur of the general population.

The last lines are:

There was a time we thought we were nothing without America. When she left, we realized all the excuses we�d been making. All the problems we�d been trying not to address. We drunk dialed our memory of America just to hear what we were thinking. We worked late and we told ourselves we had to, that the work came first, that this was an important time in our lives and that love could wait. Just wait a little longer and we�d fix everything, we�d say. Solving the America problem, our lack of attention, our disinterest in sex, our never being home, our thinking of her as a problem � it would have to wait.

[installation view of the rear of the curtained 1972 Miller-Meteor ambulance/hearse]

[text from the audio of the installation courtesy of the artists]